This is a long story about one of the most important influences in my life. The main photo depicts Bill and Polly Anna Randol visiting our Oakton home on July 1, 1992. The story begins earlier.

"Let's trick him," said Larry Harry.

"Too easy," said Dick Ristaino.

The "jeep"—the term for a newcomer—was a fine-looking fellow but dour. We did not yet see the gangling, goofy Bill with a unique humor and an artistic flair who would always live life a little off key until he met the magnificent Polly Anna, or P. A., 30 years from now.

To make matters worse, this new guy had studied the Korean language at Yale.

Wusses. Real men went to the Army Language School at Monterey, where weekends meant meaningless shooting on the firing range or cultivating the ice plant around the base commander's residence. Only wusses went to Yale where weekends meant...well...co-eds.

Harry, Ristaino and I gave the "jeep" a test of knowledge he was expected to possess working the North Korean tactical air problem. For example, if a pilot said he was lowering flaps to 45 degrees, his regiment was upgrading to the MiG-17 because the flaps on the MiG-15 extended only to 40. But instead of using actual facts like that one, we gave our test subject a fake test about stuff that wasn't real. And we waited for him to squirm. A "jeep"and a Yalie. What a combination. We were lowering ourselves.

After about twenty minutes, the "jeep" admitted being stumped. His wit and humor would become evident later, but this was not that time. We'd planned to reveal our little joke but the moment never arrived. Bill was hostile. Larry, Dick and I were enmeshed in the embarrassment we'd created for ourselves. This would not be our last practical joke together, but it was the last no one enjoyed.

When we performed our real-world duties, nobody was better than Larry, Dick, Bill or I. I'm no fan of the faux patriotism or fawning over veterans that began when we replaced the citizen-soldier with the warrior ethos. In our era the threat was real, very young men went to difficult places to confront it, and I'm proud to have been an American airman—no title means more—with men like Joe Fives, Larry Harry, Martin Doerfler, Dick Ristaino and Bill Randol.

Bill Randol, Tara Thai Restaurant, Vienna, Virginia, April 5, 2004:

Forty-four years later, Colonel Larry Harry is interred at Fort Rosencrans, all honor to his name. Dick is a retired Central Intelligence Agency and Department of State officer living with Marcia in Maryland. I'm a retired Foreign Service officer and author living with Young Soon in Virginia. Bill is a artist, wood-carver and photographer living with Polly Anna in Albuquerque—oh, how they love that hot-air balloon festival!—but for some reason they are visiting Baltimore. Why?

Why Baltimore? For the first time in too long, Bill, Dick and I are able to get together to savor spicy Thai food and get caught up on personal and family news.

The three of us sit in a corner of the restaurant. Bill explains that he and Polly Anna had some tests on him back home. They were pretty sure, then. But certainty meant being tested by the best. Bill had been visiting Johns Hopkins.

The crispy spring rolls arrived.

"I have ALS," said Bill Randol.

It was a total surprise to me but I understood what it meant. My initial reaction will forever haunt me.

Dick apparently didn't recognize the term.

Many Americans don't.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, is a disease of the parts of the nervous system that control voluntary muscle movement. In ALS, motor neurons (nerve cells that control muscle cells) are gradually lost. As these motor neurons are lost, the muscles they control become weak and then nonfunctional.

Said PollyAnna: "To the end, he remained engaged and active in things that mattered to him—family and friends (he telephoned dozens of them during his last week), music (his opera recordings were playing during the week he was approaching death), politics (we'd just sent letters to our congressional representatives a week before) and photography (I'd just mailed a calendar proposal to a publisher a week earlier)."

Bill Randol, San Francisco, 1962:

Had things gone differently, life might have begun and ended for Bill Randol with fulfillment of the American Dream—especially if looks and money were all that mattered.

He had both. His 1963 wedding to Sue Randol brought with it everything looks and money could buy for you—a suburban bungalow, paid for in cash, the required TR-4 sports car—half a decade before I would own a car of any kind—and the giant, road-hugging station wagon for those Saturday shopping days. The marriage produced two fine children—I was in the hospital when son Jeff was born in 1964 but away in Madagascar by the Jennifer arrived two years later. The marriage produced everything that any American might want although, in those dying years of the one-income household there preexisted a strong presumption that the husband was supposed to have some interest in a profession, or a career—or at least a job.

A job. You know. Nine to five.

Had Bill remained enmeshed it that trap, he would've figuratively died while remaining physically alive. He had the perfect world and it didn't interest him. Hell, Sue didn't even care for opera, one of Bill's dozens of lifelong interests. I'm writing this on Day Eighty since my own diagnosis of a fatal brain tumor: I'm going to spend every minute on the interests I love. Bill was able to do exactly that and to know freedom, even after becoming fatally ill, because he refused to be boxed in.

We'd done what our nation asked. As American airmen we'd made a difference. Today, no terrorist group has any realistic prospect of destroying the United States. In our era, men in Moscow were prepared to and could have. The American citizen-soldier stopped them.

Mustering out at Travis Air Force Base, California in August 1960 a month before my 21st birthday, I received four, one-hundred dollar bills. It was the largest amount I had ever possessed. I spent part of it to see the movie "Ocean's Eleven," with Frank Sinatra.

When Bill followed about a year later—and although he was discreet about it—he was wealthy. Bill's looks and his money were perhaps the worst possible combination for him to make the best start in post-military life. Money, especially, was a burden to the man Bill would become, as described by Martin Doerfler:

"Bill was a renaissance man. wood carver, professional photographer of great skill, long hall truck driver, auto racer (not as good), a great father to Jeff and Jennifer through all his marriages and girlfriends. He was erudite, a voracious reader, a student of history and politics and too damn pretty for his own good." Bill was wrong for a job or a career. Bill's shared experience with me as an airline agent with Pacific Southwest Airlines in 1963 was one of his last experiments with a job. Bill and I had a running wager afterwards about which of us could avoid holding a job longest.

My wish to support myself writing for magazines collided with my interest in the Foreign Service. I lost the wager with Bill in 1965.

Bill lived briefly in the Baker Acres boarding house in San Francisco where, in 1962 I met Pierre Messerli and Jerome B Curtis. One evening couples were carousing in the street. I looked out and saw Bill passionately kissing the boarding house occupant I thought was my girlfriend.

I think he had a trust fund from his father, source of the Randol surname and by then long deceased. His mother had since married an unpleasant man named Sture-Vasa. They lived in San Barbara. Their relationship with Bill was strained.

A year after Larry Harry and I hitchhiked across the United States in a westerly direction, Bill and I crossed the nation eastbound in his 1962 Corvair. Somewhere, lost now, is a magnificent photo of this great car pausing at Kingman, Arizona. There was some mean-spiritness during this journey with us arguing about trivial issues such as which ashtray to use for our Marlboro Reds. As we grew farther east, it became cold. An awful incident involving a snow tire chain wrapped around the Corvair's axle stranded us in snowy West Virginia mountains for hours. We eventually reached our destination, my parents' home in Maryland. Why did we made this trip? I no longer remember.

After Bill's marriage to Sue—all of these post-Air Force events occurred in San Francisco—came the day when Dick Ristaino dropped by and we organized an evening game of Monopoly, enhanced by heavy alcohol and practical jokes. Dick was on his way to the East West Center in Hawaii for studies toward becoming a Central Intelligence Agency officer. The discovery that Dick could cheat at Monopoly—yes, cheat at Monopoly—may have offered Sue her overdue, final clue that the American dream was not the American dream. Because of the Great Monopoly Cheating Scandal—Bill, Dick and I were all cheating merrily that evening and loving it—Dick and I were never again encouraged to darken Sue's doorstep.

We drank heavily in those days of our youth. For most of us, alcohol did not affect our later lives. For Sue Randol and for Dick Ristaino, it did.

The Randol couple tried purchasing and owning a motel—"Clear Lake Resort," on that great body of water just north of Marin County. This appears to be where the American dream came imploding upon itself. Martin Doerfler arrived for a visit to discover that Sue lived there but Bill no longer did.

Bill Randol on the move, 1962:

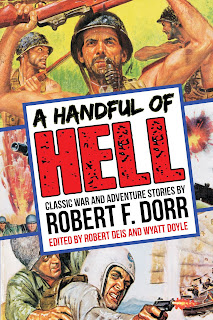

I used friends' names and likenesses in men's adventure magazine articles. Bill Randol appeared in the August 1963 issue of STAG magazine in a made-up saga of a B-17 Flying Fortress crew that was "RAMMED OVER BERLIN."

Watch for details on the Facebook page devoted to men's adventure magazines.

These magazines were popular, were sold on drugstore newstands, and promoted a mix of virility and fantasy. The articles were a training ground for authors that included Mario Puzo, Stephen King, Bruce Jay Friedman, Lawrence Block, and me. A typical story could bring the author $350.00, which is as well as some magazines pay today. I will always be grateful for what I learned writing in the men's adventure genre.

A 1966 photo, not used here, shows that Bill visited my parents in D.C. that year. I was in Madagascar.

In 1978, Bill was in northern California married to second wife Lelani. If memory serves, Lelani filled one gap for Bill: she shared his taste for opera. My photos of the two of them, not used here, plus the day I spent with them, suggest a marriage meant to last an hour and a half. I have a photo of Bill's third wife Sandra—the only one of his mates I never met. A close association between Sandra's parents and Bill's children helped to builds Bill's ties to Oregon.

Bill Randol and P.A. Randol:

Polly Anna was a Defense Department career training administrator when she and Bill met in April 1990. Bill had just moved from Livermore California to Albuquerque and went out ballooning with the folks Polly Anna, or P.A., had been ballooning with. By June 1990, they were all but living together. They were married on April 20, 1991 in a five-balloon wedding on a mesa just west of Albuquerque. If you've got t have a statistic, she's wife number four.

Bill "wanted someone to love him, warts and all," said P.A. He had finally found that soulmate. "I never had any doubt that Bill and I were meant to be together. I'm not sure what might have transpired if we'd met earlier. We would have been different people then. By the time we met, all of our life experiences had made us who we were. Absent those experiences, good and bad, we might not have been the right fit. I'm just grateful to have had the 18 years we had together. I never, never doubted his love for me or mine for him."

On October 1, 1994, I visited Bill and P. A. Randol and traveled from their Albuquerque home with Bill to the Trinity Site on the White Sands Range where the first nuclear device had been donated (on July 16, 1945), The site is typically open to the public just twice a year. I had previously visited Hiroshima and Nagasaki. My second photo depicts the Renaissance man Bill at the height of his game: Preparing to photograph the Trinity Site, Bill is a little loose, a little goofy, and as serious about his art as a stroke. He's a hugely-looking guy in a way that no longer matters as it once it did. By this point Bill has spent more or all of his estate but it no matters because it never had mattered: money never mattered to Bill, not ever, not a hoot. Marty and Carol were also visiting the Randol couple that day but chose to go to the Balloon Fiesta instead of the atomic site.

The black and white photo of airmen in Korea includes, from left, Alex Knoj, Bill Randol, two faces in the background, Dick Ristaino, Martin Doerfler and Larry E. Harry.

A photo of Robert F. Dorr. Joe Fives and Bill Randol, taken in September 1999, marks a large party for the 40th wedding anniversary of Young Soon and me. Because of an issue involving alcohol that evening, there occurred a temporary disrupt of my long friendship with Dick Ristaino. Bill Randol thought I was over-reacting. Bill's smooth voice of reason helped set the way for a reconciliation, which is why Dick and I were together for Bill when he revealed his diagnosis.

William T. Randol (May 22, 1939-March 9, 2008), you influenced my life.